Experiencing an environment triggers a two-way exchange between the environment and its observer, a process that bridges materiality and immateriality by creating what Kevin Lynch calls an “environmental image.”1 Such an image consists in a “generalized mental picture of the exterior physical world that is held by an individual”2 and it is critical in contributing to the subject’s ability to engage his/her environment, from orientation and way-finding to social interaction and emotional mooring. Environmental images are drawn both on personal—subjective—factors and on collective—objective—responses to sensory cues. “The Image of the City,” Lynch’s famous volume, sets out to investigate the latter: how the physical environment can be planned so that its corresponding image is “vividly identified, powerfully structured” and “highly useful.”3 These features account for what Lynch calls “imageability”: the “quality in a physical object which gives it a high probability of evoking a strong image in any given observer.”4 In the near future, the technology-driven rebalancing of objectivity and subjectivity in the perception of urban environments might call into question the relevance of such prescriptive approaches. This essay attempts to re-frame imageability in the context of the Augmented City and to envision and propose a new, digitally externalized, environmental image.

Objective Navigation

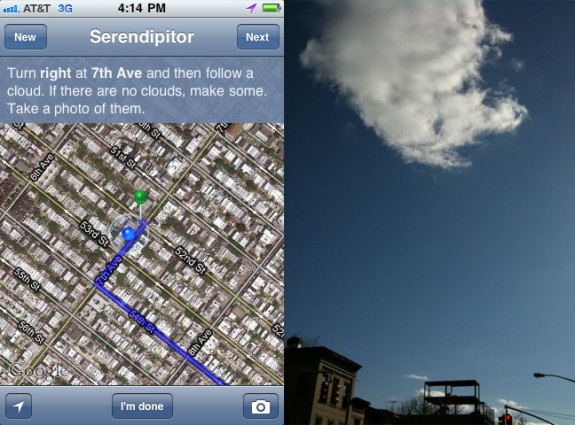

The Augmented City is a mixed urban environment where virtual and material objects entwine and are simultaneously experienced, one where cyberspace and the physical world co-contribute to the construction of reality. In this near-future cityscape, it seems unlikely that urban orientation and way-finding will rely on physical cues. Here is why: (1) Today’s widespread usage of GPS navigation systems and applications in cars and smart phones heralds the substitution of do-it-yourself way-finding in favor of reliable technology-led navigation apparatuses. (2) Digital navigation provides increased security and minimizes the probability—both actual and perceived—of becoming lost. (3) Computers tend to be more reliable than people; they have slimmer margins of error and can pick-up and adapt real-time information such as weather forecasts, news reports or service changes. (4) Satellites see farther than eyes, their vision being unbounded by environmental barriers and unobscured by darkness. Even in the absence of sensory cues, they know where the next subway station is and how to lead me to it.

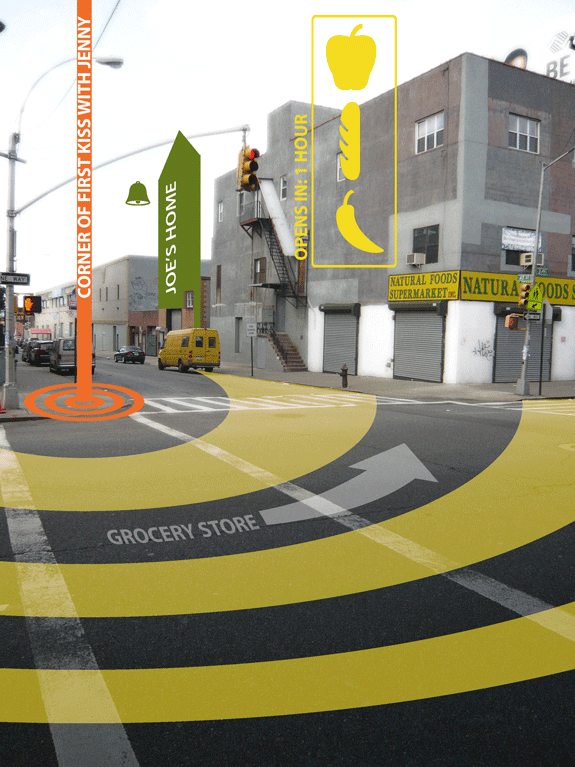

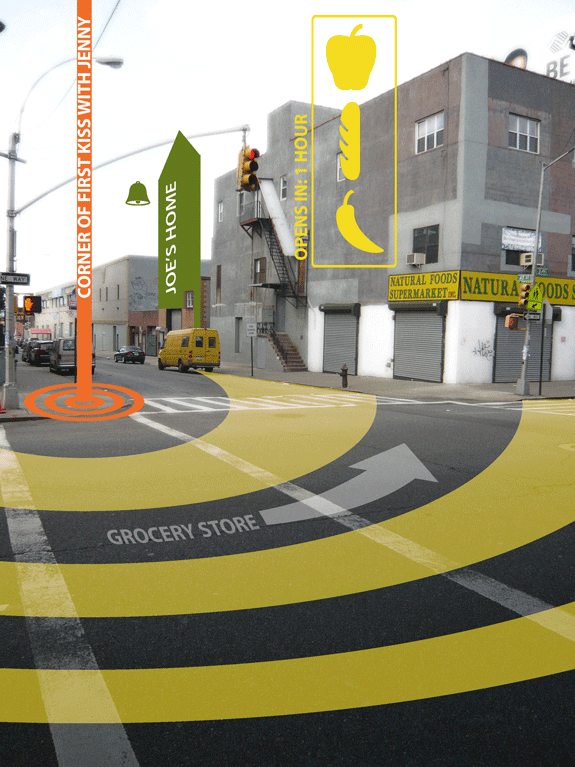

The transposition of navigational cues from matter to bits does not necessarily promote digital alienation. On the contrary, a subject’s physical surroundings are emphasized and continued by digital information overlays: their gaps filled, their inefficiencies smoothed away, their visibility augmented. The mediated inhabitant of the Augmented City must still read and interpret his/her environment in order to successfully engage it, but the necessary identity and structure—characteristic of Lynch’s paths, edges, districts, nodes and landmarks—are not embedded in the mediated object, but designed and programmed into the mediating interface.

Going one step further, we might wonder if matter-embedded objectivity is doomed. Today objects of all scales from forks to buildings to entire neighborhoods owe part of their shape and inner organization to the demand for discernable images. A door, for instance, is defined by the capacity to perform a function—open and close— but its hinges and handles are not only functional pieces of hardware, but also cues helpful to recognize the object ‘door’. In a building, the entry door is still defined by its function—providing access and connecting inside and outside— but in the context of the city the door’s success depends almost exclusively on its ability to signal presence and to be found. To this end, architects have historically employed clusters of strategic indicators: canopies, entrance plazas, variations in scale, symmetry, ornamentation and so forth. Now, in a mixed setting where indicators are predominantly digitized, how will the practice of architecture change? How will buildings organize the relation of their parts to the whole if the semantic link between user and physical building is broken? The way we understand and design the environment may be on the brink of a paradigm shift.

Of course, there is an inherent risk in replacing physical orientation and way-finding cues with electronic systems, the most obvious ones being the possibility of mechanical failure, black-outs and technological segregation, but these challenges aren’t much different from those met thousands of times by human beings employing new technologies: from the reliance on fire in food preparation or lighting to extend the day, to the use of cars and airplanes to move around and the adoption of computers to process and store data.

Subjective Domestication

The environment suggests distinctions and relations, and the observer—with great adaptability and in the light of his own purposes—selects, organizes, and endows with meaning what he sees. The image so developed now limits and emphasizes what is seen, while the image itself is being tested against the filtered perceptual input in a constant interacting process.5

The urbanites Lynch had in mind when writing “The Image of the City” were different from us and from the future dwellers of the Augmented City in significant ways. Their experience of the urban environment is implicitly counterposed to the domestic experience, one characterized by maximum perceived security and privacy, impeccable orientation and absolute control over the identity and organization of space. At home we feel safe, we are able to orient ourselves in pitch dark, and we are aware of the content of each drawer, shelf and wardrobe. In this sense, home could be re-defined as the bounded space of perfect correspondence between a subject’s environmental image and the environment. A correspondence, it is worth noting, that derives more from familiarity and habit than from an objective, coherent organization of space. Now, when Lynch’s subjects venture out of the domestic sphere, they leave behind not only the constellations of objects and functionalities with which they appropriated their home, but the very capacity to appropriate space with similar pervasiveness. On the contrary, the contemporary electronomad can carry along with himself/herself, in the form of bits and networks accessed through portable and wearable devices, many of the functionalities and belongings once associated with domestic life.6 Furthermore, if, as inferred, real time information overlays will absorb and broadcast part of the identity and structure of the built environment, the mediated/mediating citizens of the Augmented City will be endowed not merely with control over environmental images, but with control over the environment itself. Extreme customization is the ability of the technologically equipped subjects of the near future to customize their own perception of the urban environment through digital curatorial channels, locational feeds and mnemonic geographies. It is an electronic filter capable of mediating the cityscape according to one’s interests, memories, social values, group associations, tastes and so forth.7 In conclusion, we can predict that subjectivity will play such an extensive role in the experience of mixed space, that its virtual layers and the subject’s corresponding mental images will often overlap and merge. The environmental image of the future will be an externalized digital representation of customized objective and subjective cues; an electronic spatialization of identity, structure and meaning; a ubiquitous dimension of home.

Notes:

1) See Andrea Mubi Brighenti, “New Media and the Prolongations of Urban Environments” in Convergence 16 (November 2010)

2) Kevin Lynch, The Image of The City (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1998)

3) Ibid.

4) Ibid.

5) Ibid.

6) For more on electronomadics, see William Mitchell, Me++: the Cyborg Self and the Networked City (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2003) 7) For more on extreme customization, see Simone Ferracina, Organs Everywhere No.1, Augmented Selves, organseverywhere.com/past/issue1/ (accessed January 30th 2011)

Image by Organs Everywhere. Apple/Bread/Pepper/Bell pictograms by The Noun Project are used under a CC BY license. This article was first published in Lo Squaderno No.19, March 2011